Last week (November 19th) an article was published in Geekwire that got my blood boiling. The article in question was written by Jeff Reifman. Jeff was a program manager at Microsoft and is currently an independent technical consultant living in Seattle. Earlier this year he wrote a (very good) post on his personal blog about how the growth of Amazon is so significant that it has measurably influenced the gender ratio of the single people in Seattle. The post went viral and Jeff made a local name for himself as a writer.

This, I assume, gave him the platform which allowed his latest piece to be published in Geekwire. Where his first piece was an interesting data-driven look at the impact of a single company on the demographics of a city, this new post is just a diatribe. The internet is full of ignorant venting, so why did this particular post bother me so much?

- It’s getting a lot of airplay – so it’s ignorance with an audience

- It’s coming from someone who previously produced a nice piece of data-writing, which is disappointing

- Its latching onto a two trends I’m seeing more and more recently: “Big Company = Evil” and “Change is bad”. Both of those memes have been around for a long time and will never go away, but it’s disheartening when the tech media starts stroking that fire rather than educating

- In the three days after his post I heard slightly different versions of the same argument from two very different sources. One was from a friend’s facebook feed complaining about similar problems in Vancouver. The other was from a Lyft driver who was lamenting the changes in South Lake Union.

For those four reasons I’m putting aside my standard data-driven marketing blog post this week for a monstrously long (for me), 8000 word rebuttal to Jeff’s piece. This article started out as a point-by-point rebuttal of Jeff’s article (and still ends that way), but it has expanded in its final form as a sort of manifesto against the idea that growth, change and improvement are bad (because change leaves people behind). Change has been leaving people behind long before automobiles replaced the carriage. The point that no one cries for all the unemployed blacksmiths these days has been made ad nauseum, and I won’t spend any more time on it than I already have. Instead I will use Jeff’s core arguments as a structure to explain why I believe Amazon is doing a ton of good for the city of Seattle (and the world for that matter).

On with the essay.

Jeff’s Arguements

Jeff starts with the fact that Amazon’s office space, if fully utilized will cause it to employ 45,000 people, or 7% of Seattle’s workforce. He then states that this will cause (or ‘fuel’), “an unaffordable traffic-filled metropolis dominated by white males and devoid of independent culture.”

The rest of his article tries to explain why this will happen, why it is Amazon’s fault, and why this is bad. His arguments are internally contradictory and based on hyperbole. Before I dive into tackling these arguments one-by-one, I’d like to start with taking on the complaints themselves:

- Unaffordable

- Traffic

- White Males

- No culture

All of those words are very charged. Obviously no one wants a place that they can’t afford. No one likes traffic. Unless you are in the KKK, white males are a sign of non-diversity (which is bad). And if you had to choose between culture and no culture, I’ll bet north of 90% will take “Culture please!”

But before we assume that all those things are bad, it might make sense to examine them a little critically (maybe with different ‘non-charged’ words).

An unaffordable city means that people can’t afford the rent or real estate prices. Is this possible in a free market economy? Of course not. If no one can afford rental property, the owners will reduce the price so it doesn’t sit empty. If no one can afford to buy a house, house prices will come down until someone can (or the people that own it decide to sit on it and not sell).

People can obviously afford rent and housing prices in Seattle. In fact, I’ve heard from my friends looking to buy that houses priced under $1M (most of them) are often turning into bidding wars and they have to make offers on the spot if they have any hope of getting the place.

So people can afford to live in Seattle. In fact given the population increase and the utilization of housing, MORE people can afford to live in Seattle than ever before.

But that’s obviously not what he means. He means that prices are higher than they were before. And that prices are so high that people who are lower on the income scale can’t afford the housing costs in the city.

This is bad, right? Gentrification driving out people who have been renting for years and now can’t afford the new prices that the new Amazon employees are able to pay.

What is the alternative?

Easy. Prices do not increase.

Well, we know what happens when prices go down. Investment banks collapse and the government needs to bail out the automotive industry. Pretty sure that’s not good.

It’s not always true that the opposite of bad is good, but I think in this case it is.

Why do prices go up in a market economy?

Two reasons:

- Demand has gone up

- Supply has gone down

Since supply isn’t dropping (A quick look at the Seattle skyline tells you it is going up), demand must be going up faster than supply in increasing. What causes demand to go up?

- Existing ‘customers’ are willing to pay more for the product

- Due to a higher quality product; or

- Due to more disposable spending (i.e., they have more money and choose to spend it on this thing they like)

- New ‘customers ‘ wanting to buy the product

1(1) seems like a pretty good thing. If the city were to make the city better without raising taxes then hopefully we would all be in favor of it.

In practice this isn’t always true. When I was living in Center City in Philadelphia a developer was looking to build a move theater nearby (there were no movie theaters in the neighborhood). Even if you don’t love movies, a movie theater is still better than an empty building (which it would be replacing). And yet the street poles were covered with pamphlets protesting the development. The argument was that if the neighborhood got a theater, then it would be a better place, which would allow landlords to increase rents, which would make it less affordable for the people living there.

Basically their argument was: “Don’t make the city better.”

If there is interest I can expand on that in another post, but for now I will assume that readers here prefer making cities (and the world) a better place rather than a worse place.

1(2) is less clear. If people have more money because asset prices are inflating, this could just be an artificial bubble (which we saw leading up to 2008). We may or may not be able to identify these bubbles in advance, and it may or may not be true Amazon is creating a bubble (it is one of the arguments Jeff throws against the wall in his tirade about the company) but let’s agree that bubbles are not good and if Amazon is creating one, that is also not good. So if the increase in demand is due to an asset bubble we have reason to pause. Let’s come back to that later when I work through Jeff’s specific arguments.

The other reason 1(2) happens is that people get truly richer (as opposed to fake ’bubble’ richer). When people get richer they have two choices: Spend the money or save it. In practice people usually do a bit of both. Whatever they choose to spend their money on will experience an increase in demand. Often when people get richer they choose to live in nicer places (or move out from their parent’s basement) – when they do that they will increase the demand for real estate and housing (and rental costs)

I know some people are against the idea of some people getting richer than others, but for now I’m going to assume that making a significant number of people in the city more well off is a good thing (vs. stagnating and/or decreasing incomes)

Finally, (2) basically says “If your city is a better place, people who don’t live in the city currently may want to move there now that it’s a better city.”

Unless we want to prevent internal migration, that also seems like a pretty good thing.

At this point, assuming demand is not increasing due to a bubble, you should be FOR increased demand (unless you are (1) Against making the city a better place, (2) Against making current residents richer).

In fact it’s even more simple that that. (1) and (2) are two sides of the same thing. If a city has opportunities to make people richer (great jobs for example) that’s part of what makes a city ‘better’. A big reason people move to a city (why they think it is ‘better’ than their alternatives) is that they can get a great job there.

Assuming flat supply of housing, raising real estate prices are a sign of a city that is becoming a better place to live – at least defined by what people are willing to pay for.

It’s easy to get cheap housing in the United States, just move to one of these cities: Top 10 Cheapest Cities to Rent an Apartment

The median rent for a two bedroom apartment in Wichita, Kansas is $650/month. You could live by a river and work for an airline-parts manufacturer. Or move to Tucson Arizona to live by the mountains for only $628/month.

But you don’t want to live in Wichita you say? You want to live in Seattle? Why? Because Seattle is awesome! How do I know Seattle is awesome and it’s not just my personal opinion? Because people want to live here. They want to live here so badly that they have driven up the price of real estate!

When people say they want lower prices, what they really mean is that they want to live in an awesome place but not pay what living in an awesome place costs. A Complaint about higher prices is really a complaint about higher demand which is really a complaint about change.

Let’s Talk about Supply

There is only one thing that will keep rents down while a city becomes a better place to live: Supply.

If you build more housing it will, all things being equal, reduce the value of existing housing. This is a big reason why existing home owners almost always protest new development. They say things like, “It will increase traffic” or “There won’t be enough parking”, but it all comes down to the fact that it will reduce the value of the housing that is next to the new development.

If yours was the only waterfront home and someone wanted to live on the waterfront, they would have to buy from you and you could extract as much as he or she would be willing to pay. But if that same person could build a new house next to yours on the waterfront, you now can’t charge more than the cost to build that house.

Increased housing supply drives down existing housing values (and rents).

That is part of the reason why entrenched interests make it hard to develop. San Francisco is the worst for this. Environmental regulations, building permits, zoning, etc. all make it more difficult to build. When it is more difficult to build, less gets built – which keeps prices high.

You really want housing to be more affordable in Seattle? Then ask the government to make it easier to build. Not just low-income housing. Any housing. Imagine if there were 100 more buildings in Seattle like the Escala. You can bet that the demand for units in the Escala would decrease (and be spread among the 100 additional buildings) and the price of units in the Escala would come down. If the Escala is cheaper, someone who was looking to buy in 98 Union might say, “Well, if it’s only an extra $20,000, why don’t I live in the Escala instead of 98Union?” Now 98 Union [and buildings like it] needs to lower their prices to compete. And lower prices at 98 Union means that someone who was planning to move into Capitol Hill might reconsider now that 98 Union is so affordable, which drives down prices in Capitol Hill.

But isn’t Seattle building like crazy? It sure looks like they are from all the cranes I can see from my office window. I think there are two reasons this increased supply is not (yet) driving prices down:

- It didn’t happen fast enough. Development stopped in 2008. It took a while to get going again, and it takes a long time to complete a building.

- Demand is growing even faster than the cranes are building

We are in an adjustment period. Assuming that development is allowed to continue (a big assumption) then prices will come down to an equilibrium.

But given that the real estate footprint itself is limited (there is only so much land within a mile of Pike Place Market), and assuming that demand for living in a specific place in the city will go up as the city gets better, prices will still go up. It’s just that if you are willing to compromise to live a little further away from your ideal location, more supply should spring up to make that no less affordable than living downtown was before.

(The concepts of using property prices as a way to understand the quality of a city were taken from one of my favorite professors at Wharton: Robert Inman)

But wait. If Seattle is getting so much better, why the crazy traffic? Traffic is definitely making the city worse. I haven’t seen firm data, but it would not surprise me if traffic is objectively worse in Seattle than it was 5 years ago. The fact traffic is worse is driving DOWN real estate prices (and rent). That should be obvious. If you had two choices of places to live that were identical and one had a really bad commute to work and one was really easy, it’s pretty clear which you would choose. But what if the really bad commute was a lot cheaper? Maybe you would change your mind. How much cheaper? It would depend on your personal preferences and how bad the traffic was. But we can be pretty certain no one would pay more for worse traffic.

So traffic drives down property values. But property values are still going up. Why?

Because the city is getting better faster than the traffic is getting worse. People are willing to put up with the traffic because of all the other good things Seattle has to offer (like jobs).

But couldn’t we make things even better by building great public transport?

Before you get too excited, remember: If we manage to build better public transport (and we can do it without raising taxes), then that will make the city better. Then what happens? Demand goes up and property prices (and rents) go up…

I keep saying ‘without taxes going up’. I do this because if taxes go up (without adding benefits), it makes the city worse. Go back to your two choices: Two identical places, one with no taxes, the other charges you $1000/year. Pretty clear which choice you will make.

Let’s say we can’t build more public transport without raising taxes (a realistic assumption). So the city raises taxes and invests those dollars in better public transport. Let’s say two breakeven. The taxes reduce property values but the better public transport raises property values. Basically the “people” (those who generate or reduce the demand) decide that the city got what it paid for (ideally the city is finding things to spend on that are better than that. They spend $1 in taxes to create $2 in value for the city – which would eventually increase demand for their city – and raise property values. Unfortunately most politicians are more interested in getting re-elected than they are in creating value for their citizens)

Maybe Seattle can do this.

Before we do though, it’s worth looking for a benchmark to see how we are doing right now. Everyone ‘knows’ Seattle has terrible public transport, but is there a metric we can use to understand just how bad? Like most things, it’s easier to go from terrible to bad than it is to go from great to awesome. There is diminishing returns on everything – including public transport. But if Seattle’s public transport is really really terrible, then we might have the opportunity for some low hanging fruit.

One way to measure the quality of public transport is to look at how much it’s used. If no one is using public transport it’s pretty clear it’s not meeting anyone’s need. If everyone is using it, it’s a sign that it’s likely doing pretty well. The good news is we have this data. The American Community Survey asks the question across the country annually: “How do you usually commute to work?”

It turns out that about 5% of people in the US commute using public transport. In Seattle the number is about 20%. That sounds great, but it is still pretty low compared to cities we think of with great public transport systems:

- New York: 55%

- Washington DC: 37%

- Boston: 35%

- San Fran: 32%

- Chicago 27%

- Philadelphia: 25%

So Seattle has a significant gap to the leaders, but we are still well ahead of most of the country:

- Kansas City: 1%

- Cincinnati: 2%

- San Antonio: 3%

- Atlanta: 4%

- Denver: 8%

- Portland: 12%

Seattle has the 7th highest rate of public transport commuting in the country. We may not be awesome, but we are a long way from terrible.

But why aren’t we better? What’s stopping Seattle from having the public transport usage of New York City?

One word: Density.

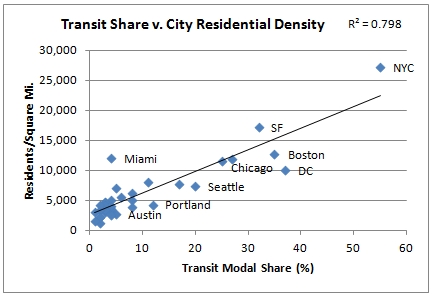

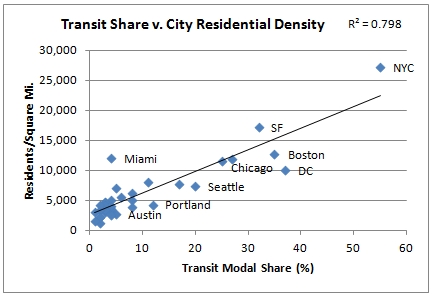

Here is a chart of the ACS data combined with urban density data (granted this is from 2008, but the story still holds):

The x-axis has the share of commuting done by public transit. The y-axis is the population density of the city. Not surprisingly, the denser the city, the better the public transit.

But it’s not a perfect fit. The cities that are below the line are cities that have managed to achieve more use of public transit than their density would suggest. #1 on this ‘over-achieving’ metric is Washington DC. #2 is Portland. #3 is Seattle.

For its population density, Seattle is the third highest user of public transit.

Maybe we aren’t so bad after all? (And maybe the reason we complain so much about it is that we are using it at a much higher rate than comparable cities. People in Houston don’t complain about their public transit – they just ignore it…)

But let’s not rest on our laurels! How do we make public transit even better?

The obvious answer from this chart is to increase population density.

Which is exactly what Amazon is doing (and what Jeff is complaining about).

It’s the old argument that the world would be a much better place if there were a lot less people. If there were no people I would be able to get tickets to the Football game without paying a huge amount of money and I wouldn’t have to wait in line at the Starbucks. But this forgets the fact that without the people there wouldn’t be a football team – or a Starbucks.

It’s easy to move somewhere where there are less people. It just turns out that that is NOT what people want. They want the advantages that come with lots of people more than they dislike the disadvantages that come with lots of people. They just like complaining about it.

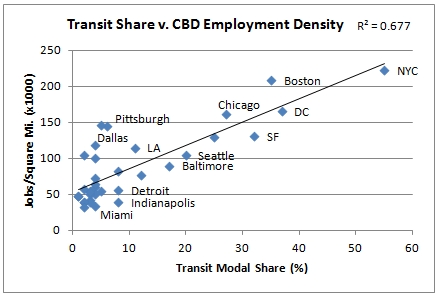

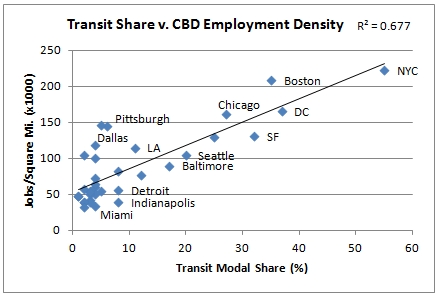

There is one more way to improve public transport (I know I said “one word” but there are actually two): Increase the number of jobs in the downtown core:

Guess what else Amazon is doing?

(Charts in this section were from Charlie Gardner on his blog oldurbanist)

Jeff says Amazon only hires white men. Quoting from his post: “While the company reports 63% of its worldwide workforce is male, it’s likely closer to 75% male in the company’s Seattle technology headquarters; that’s the company’s overall managerial ratio and close to Microsoft’s technical ratio”

First: From walking around South Lake Union, I’m pretty sure Amazon hires a lot of Indian men. Either that or that ethnic group really likes the fruit at Portage Bay Café. Let’s assume that his complain about diversity is really a complaint about only hiring “White AND Asian men.”

Rather than addressing this directly I will throw it to (Founder of Netscape and Silicon Valley darling) Marc Andreessen. This quote is from an interview with New York Magazine. When he was asked about why Silicon Valley is so un-diverse he replied:

“I think the critique that Silicon Valley companies are deliberately, systematically discriminatory is incorrect, and there are two reasons to believe that that’s the case. No. 1, these companies are like the United Nations internally. All the diversity studies say that the engineering population is like 70 percent white and Asian. Let’s dig into that for a second. First, apparently Asian doesn’t count as diverse. And then “white”: When you actually go in these companies, what you find is it’s American people, but it’s also Russians, and Eastern Europeans, and French, and German, and British. And then there are the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Thais, Indonesians, and Vietnamese. All these different countries, all these different cultures. To believe in a systematic pattern of discrimination, you’d have to believe that we’re discriminatory toward certain people without being discriminatory at all toward an extremely broad range of ethnicities and religions. Because of Pakistanis, we’re seeing a higher-than-ever proportion of Muslim employees in a lot of our companies.

No. 2, our companies are desperate for talent. Desperate. Our companies are dying for talent. They’re like lying on the beach gasping because they can’t get enough talented people in for these jobs. The motivation to go find talent wherever it is is unbelievably high.

There are two fundamental problems that are resulting in what a lot of people believe is discrimination, and these are the problems that I think need to be solved. One is inequality of education. If you come up through a path that’s sort of a stereotypical upper-middle-class American path and you go to Stanford and you get a really great technical education and your professors really care about you, then you come to Silicon Valley and you’ve got the skills and you’re golden.

But, of course, most people in the world—including most people outside the U.S. but also people in the U.S., like where I grew up in rural Wisconsin, or people in the inner city—never have access to that kind of education.”

Amazon isn’t discriminating any more than Silicon Valley as a whole is discriminating; they are hiring all the talent they can find. The real issue is the education long before people get to Amazon. But asking Amazon to solve the US education system might be a little bit much?

So maybe I convinced you that Amazon isn’t discriminating. And that while it might be raising property values, that’s only because it’s making the city a better place to live. And while traffic might be getting worse in the short run, it’s still a better place to live than the alternative, and in the longer term the increased density will make public transit even better.

But what about culture? You can’t measure culture!

And even if they aren’t discriminating, they are still increasing the white-ness (plus Asian-ness) of the city. They are increasing the male-ness of the city. And they are driving poor artists out of the city. Eventually we will turn into New York.

Wait a minute. Does New York not have culture? Did the high rents created by the jobs in the finance industry destroy the culture of New York City?

Not so much.

When the World Cities Report on Culture chose a single city from each country to compare, America’s city was New York. When PropertyShark looks at number of cultural attractions New York had the most (2,693) (Seattle had the most per capita). TravelAndLiesure took their ranking system to the public and just did a survey. New York came on top again (followed by DC, Boston, Chicago).

“But Ed, those are all based on tourist attractions and the impressions of tourists. That isn’t real culture. Real culture is the number of people working as artists in a city. And real artists can’t afford to live in a place like New York.”

Except they can.

The American Community Survey has a category called “artists and related workers” – it basically means both employed and self-employed visual artists. Being a visual artist is a tough road in America. There are only 237,000 of them in the country. Guess where they live?

210,000 live in cities.

Which city has the most? For all the talk of the prices in New York driving out artists, it has more artists than any other city in the country.

“But Ed, that’s just because it has more people in total.”

Exactly! As a city does better it attracts more people, but it doesn’t eliminate artists, it just increases everyone else around them. New York might not have the highest per capita artist total, but it has the most people in one place doing art. And that allows a community to form.

Santa Fe, New Mexico has the per capita number of artists in the country. But when I was doing stand-up comedy, no one dreamed of going to Santa Fe. If you wanted to really learn stand-up and/or improv comedy you moved to New York, or Chicago, or LA. No one cares about per capita.

(Seattle by the way has the 5th highest total of artists in the country. Anyone think that if Seattle grows it’s population 50% due to Amazon we will have less artists living here?)

Jeff’s Post

I just spend >4000 words on my introduction. It should cover most of Jeff’s arguments, but there are a few loose ends to tie up. Let’s work out way through them:

In “Seattle Today” he starts by complaining about the number of construction projects and the poor public transit (both complaints in the same paragraph). I think I’ve covered that in enough detail. Jeff: More construction will make public transit better. Just think about it.

He then complains about all the white people Amazon is hiring (covered) before throwing in the barb that women in the country are paid less than men. (Yes. But what does this have to do with Amazon, or even with Seattle? And the data is not nearly as clear as it is often made out to be.)

The Future is Obvious

Seattle will have more tall buildings (bad? Yes, according to Jeff because it will mean worse views for many buildings). And people will be wealthier (Also bad because it will drive out artists). I think I’ve covered both issues, but he covers himself by saying, “Some may find this exciting… But it’s the nature of the changes that concern me.”

Let’s dive into these natures.

Wealth Gap

Across the country (nothing to do with Seattle again) 5% of Americans control 60% of the wealth. He then claims this is what is driving an increase in crime in Capitol Hill and that February had the highest number of robberies ever (and two gun murders at almost the same time)

Wow. That sounds bad.

Let’s talk about crime for a few paragraphs:

“The most robberies”

Does the most matter? The city with the most robberies in the US in New York. I don’t need to look it up. It’s the most because it’s the biggest. Just like it has the most artists. The difference is, the absolute number of artists matter (number of opportunities and variety of art available, number of connections an artist can make), but in crime what you care about is the chance you experience it. You care about the per capita crime rate.

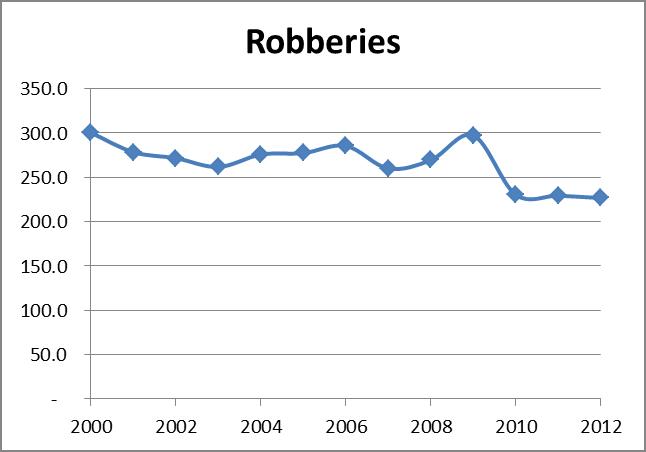

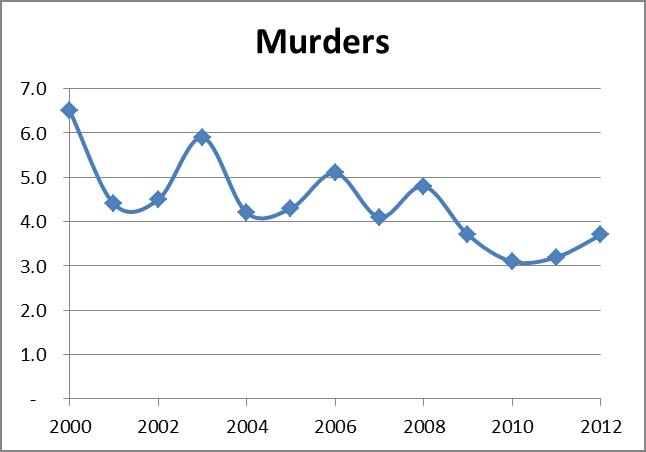

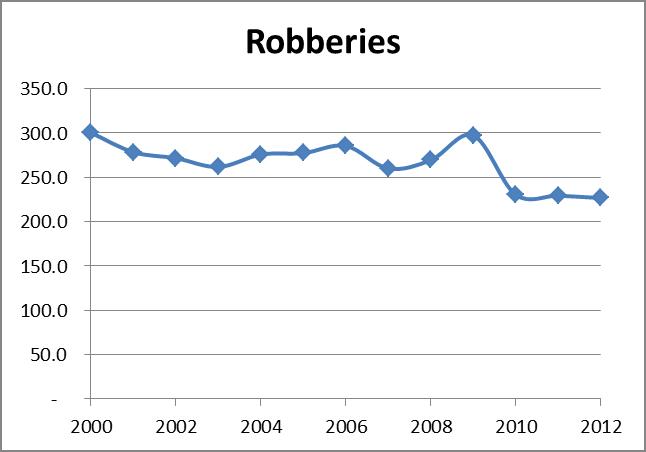

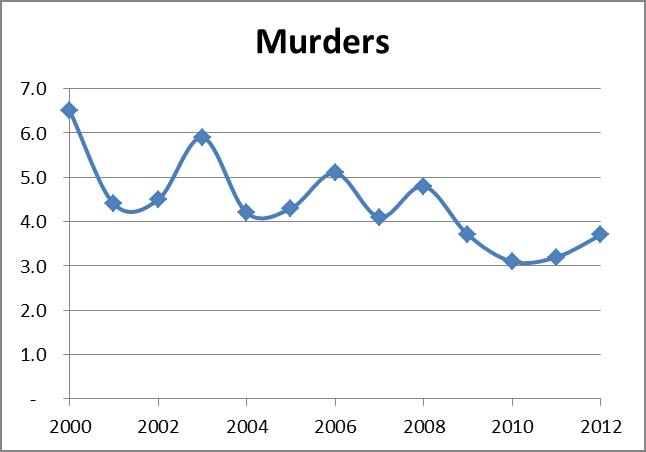

Guess what? Per capita crime in Seattle has been going down for more than a decade.

Here’s robberies (Robberies per 100,000 population):

Two things you should notice:

- It’s going down

- It’s noisy. 2009 saw a big increase in robberies vs. 2008. That wasn’t the start of a trend, it was just random fluctuation. 2010 had the lowest robbery rate in recorded history.

It’s just not true that crime is increasing in Seattle. And looking at a single month in a single neighborhood is a nice way to scare people, but it’s a terrible argument.

Note: One of the issues with crime statistics is that there is a reporting problem. What if crime is going up, but police aren’t recording it? That’s a big issue with rape for example. It could be increasing, but being covered up. Or it could be decreasing, but being brought out in the open causing the number of reported incidents to go up. The normal way to solve this is looking at murders as a control. Murders are really hard to ‘not report’ so if the murder rate is moving in a different direction than your other crime statistics you might have a problem. Since Jeff complained about the murder rate in Seattle too, let’s take a look at that graph:

Yep. Looks like that is dropping too (and yes it went up from 2011 to 2012, but the ‘n’ is very very low. You have to be careful with low ‘n’ statistics as you know if you have been a regular reader of this blog)

Now that we’ve put crime to bed, let’s move on to his next argument:

“I’m not saying that Amazon shouldn’t grow and that others shouldn’t benefit from the opportunity, I just believe the company’s growing irresponsibly and [sic] beginning to have an irrevocably damaging impact on Seattle’s character and quality of life.”

Got it. So all those earlier complaints about growth were just to get people’s blood boiling. You actually have no problem with growth. You have a problem with their irresponsibility.

What exactly is Amazon responsible for?

Political Influence

Now we get to the heart of his argument. “Microsoft avoids paying taxes”. “Boeing gets tax breaks as a form of “legalized corruption””. This gets right into the argument that companies should stop holding their assets overseas and just bring them back to the US to be taxed. And that they shouldn’t use tax “loop-holes” to avoid paying tax. I wonder how many people who believe that choose not to deduct their mortgage from their taxable income or choose to forgo their deductions for their dependents. Asking companies not to use ‘loopholes’ that lawmakers create is asking managers of those companies to steal from the owners. If I owned 100% of Amazon and I asked the management to minimize my taxes, and they said, “No. that would be legalized corruption and unethical” I would say, “Fine. Minimize my taxes and then pay the difference out of your own pocket.” It’s really easy to tell someone else to give away their money. It is a lot harder to throw away your own.

I fully agree that politicians should eliminate deductions and have a much simpler tax system, but calling people who follow the rules unethical is pure political bating.

Here is a nice old quote I found from Bryan Caplan’s blog that is still relevant:

“I want to ask a question. What is a loophole? If the law does not punish a definite action or does not tax a definite thing, this is not a loophole. It is simply the law. Great Britain does not punish gambling. This is not a loophole; it is a British law. The income-tax exemptions in our income tax are not loopholes. The gentleman who complained about loopholes in our income tax – he did not refer to the exemptions – implicitly starts from the assumption that all income over fifteen or twenty thousand dollars ought to be confiscated and calls therefore a loophole the fact that his ideal is not yet attained. Let us be grateful for the fact that there are still such things as those the honorable gentleman calls loopholes. Thanks to these loopholes this country is still a free country and its workers are not yet reduced to the status and the distress of their Russian colleagues.”

–Ludwig von Mises, Defense, Controls, and Inflation

But back to Jeff.

He jumps back onto his public transit complaints and adds that we should be taxing development more to pay for better public transit. I’m fine with the idea of better public transit, but remember, if you make development harder you will get less of it. If you get less development your density will be lower and you will get… wait for it… less public transit. Not so easy is it Jeff?

This Jeff doesn’t like Jeff Bezo’s politics. He doesn’t like that Bezos gave $100K to fight a new income tax in Washington. Granted: That tax would hit Jeff personally and cost him a lot of money. But it would also hit Amazon. One reason Amazon can attract employees here is there is no state income tax. If the income tax in Washington had been has high as California I likely would never have moved here (or realistically the company that brought me here – Expedia – would have had to pay me a higher salary. And on the margin those higher salaries that they would have to pay would reduce the number of people they could hire).

So income tax in Washington would be pretty bad for Amazon. $100K doesn’t seem like enough of a donation – regardless of personal politics.

Amazon also gave $25,000 to fund an initiative to improve bus service (public transit in the city). The initiative failed. Somehow Jeff insinuates this is a bad thing too as it means even Amazon thinks current public transit isn’t good enough. But why Amazon donating to the cause signals their irresponsible growth is a lot less clear.

Back to diversity

Jeff has already shared all the data on diversity he has to offer. Now he dives into colorful stories. A woman got an interview at Amazon but did not get a job offer. She takes to local media to claim Amazon’s interview process is flawed (among other things it was five hours long! Oh dear! And no one offered her a bathroom break. Um. Maybe Amazon is looking for people with the initiative to ask if they can go to the bathroom?)

Other women complain that they don’t like dating engineers. I can understand why having more engineers move into the city would be bad if you hated engineers. I personally don’t understand this as I married an engineer and she is wonderful. I also wonder if this woman would be complaining about dating investment bankers in New York, service workers in Vegas, insurance agents in Hartford, entertainment folks in LA, and farmers in Idaho. Turns out there is a lot of diversity within any job class. When the problem is “everyone else” maybe it’s time to look in the mirror?

(Or to be fair, maybe her personality just doesn’t mesh with the common personality traits of engineers. Maybe the best thing for her love life would be to find an oil-man in Dallas. It might be worth her long term happiness to try, rather than complaining?)

Jeff has one last diversity attack before he moves on:

Amazon is driving up hate crimes against the LGBTQ community.

That’s a heck of an accusation, and what caused one of my good (gay, Amazon-working) friends to share Jeff’s article on facebook with a comment. Rather than argue this myself I’ll just quote his post:

“In an effort to somewhat balance this very slanted article, I’d like to say I’m personally very thankful/proud that Bezos gave $2.5 MILLION DOLLARS to help fund the campaign for marriage equality in WA – the first state to have this right passed by popular vote. Insinuating that a rise in LGBT hate crimes and gun violence is because of Amazon is really offensive (among other awful statements about Amazonians like me.) In other news, you are all invited to attend this Amazon-funded gala where 100% of proceeds benefit a local gay-straight alliance youth chorus: http://2014glamazongala.eventbrite.com/”

(Just one thing: $100K to fight the increased taxes is self-serving in that it helps Amazon attract workers. $2.5M to fund marriage equality also helps attract workers – both the LGBTQ community and those who support the community (which includes most tech workers). Both help Amazon, but one amount is obviously MUCH higher than the other. Still say Amazon hates diversity Jeff?)

But Jeff has just touched the surface so far, “But what about at a deeper level?” he says…

Confrontational Culture

Next Jeff starts blaming Amazon for the “Seattle Freeze”. For those not aware, the “Seattle Freeze” is the belief that people in Seattle are really nice but they are also cliquish and you won’t get an invitation to their place for dinner. It’s hard to make good new friends here.

I moved to Seattle in 2009 and I found at least part of the stereotype to be true. I joined an ultimate Frisbee team to meet people and while I had a great time playing with them on the field, it didn’t turn into any off-field friendships (unlike similar situations where I’ve played in other cities). Over time I developed a theory on this:

Most people in Seattle back in 2009 had grown up here or been here a long time. They had a long-time friend group, and there wasn’t a strong need or desire to bring in new people who just moved to the city. They were friendly, but no, they didn’t need to invite you into a friend circle that was working very nicely thank you very much.

It took many years (and meeting my future wife), but I now have a very broad friend group in the city. What changed? New people. In the last 6 years Amazon has brought a TON of new people into the city. Unlike people who have long-standing friend groups, these people are looking to make new friends.

Amazon isn’t increasing the Seattle Freeze with their culture, they are dramatically reducing it with changing the mix of the city.

It’s hard to make friends later in life after you have left school and gone on to your second or third job. But the easiest way to have it happen is to be surrounded by people who have to build new friend groups at the same time you are. Thanks Amazon.

Amazon mistreats employees

Amazon works its employees hard. So does McKinsey. So does P&G. What all these firms have in common is that after you have spent some time there your personal brand improves. People know that you are able to work hard. And people know that you have been trained in the “Amazon” (or “McKinsey” or “P&G”) way of doing things. Amazon doesn’t hide it. No one takes a job at Amazon and then says “Wait. You want me to work hard?” (Okay. Maybe some people do, but they were hiring mistakes).

I don’t work at McKinsey anymore and I will never go back to that lifestyle, but I believe the choice to work that hard for four years of my life was definitely worth it. Can we give Amazon employees the same benefit of the doubt? And if they don’t want to work that hard, maybe they should quit and get another job? That’s the beauty of our capitalist system.

“But Ed, they are quitting. Jeff says the average employee retention is 1 year vs 4 years at Microsoft.”

Great! Even more benefit for Seattle.

If Amazon hired all these talented people and then kept them inside Amazon that would be good for the city. But even better for the city is attracting these talented people to the city, training them for a year, and then setting them loose. Wikipedia lists 19 “Notable” companies founded by ex-Amazon employees. And that doesn’t include all of the ex-Amazon employees filling the senior and middle-management ranks at technology companies across the city. You would be hard pressed to find a technology company in Seattle that doesn’t have someone from Amazon somewhere in the mix.

Philanthropy

According to Jeff Amazon gives 0.5% of sales to charity. My first reaction to that is that I can’t believe it’s that high. He must be making a mistake. Amazon is a retailer. Which means it operates under some pretty tight margins. It’s not uncommon for retailers to have 10% or less gross margins, from which they need to pay for their fixed costs (including logistics, real estate, etc.). On a good quarter Barnes and Nobel will make 2.5% profit (on a bad quarter it is -2.5%). If they were to donate 0.5% of 2.5% that would be 20% of their profits.

(I won’t repeat my earlier argument that management choosing to give away profit that is owed to the owners is not that different from stealing. It’s fine if individuals want to make donations but getting people to donate other people’s money is just an easy way out – especially it’s not your money being donated)

Jeff also praises Bill Gates. How soon we forget. Bill only became a philanthropist late in his career. For decades he led Microsoft that was often accused of being stingy. Amazon is still in the very early stages. Every dollar they donate is a dollar they aren’t investing in future growth and innovation.

Another quote from Jeff:

“Researching this piece I was most struck by a side note in Brad Stone’s Business Week expose, “New hires get a backpack with a power adapter, a laptop dock, and orientation materials. When they resign, they’re asked to hand in all that equipment—including the backpack.” If push comes to shove Seattle, expect Amazon to treat us with the same regard.”

What does that mean? If Seattle quits Amazon they will demand their laptop bag back? I’m sure there is supposed to be a metaphor in there somewhere, but I have no idea what that metaphor is…

(By the way: Giving your laptop and power cords back when you leave a company is pretty standard. I’ve never heard of a company not asking for them back. Giving them back in the laptop bag rather than handing them back a loose pile of cords seems like a polite thing to do. I’ll bet if you lost the bag for some reason Amazon isn’t charging you for it. Give me a break.)

Amazon is a bubble

Ah. We are finally at some meat. As I said early in this essay: If all this growth is only a bubble maybe we will be in trouble. Amazon goes bankrupt. Housing prices crash. Everyone moves away (on the upside: Seattle traffic will disappear and rent prices will come right down… Wait a minute: Aren’t those the two things Jeff wants to happen?). Really Jeff isn’t making a argument so much as throwing every Amazon complaint at his computer screen. “Amazon isn’t profitable” is just another complaint about the company.

(Want to know how to make Amazon even less profitable? Have the employees work less hard, have the taxes in Washington State go up and have Amazon give more to charity. Just sayin’.)

This post is long enough without a defense of Amazon’s secretive investment practices. But know that if Amazon capitalized and spread out the expense of all their marketing and R&D over 5 years instead of 1, their EBITDA would look a lot better. Their cash would not – but that is because they are taking every dollar they have available in cash and investing it in ROI positive opportunities (at least to the best of their abilities). It’s a very reasonable strategy that many could agree or disagree with (For example you could contrast it with Apple which holds onto a lot of its cash for opportunistic opportunities).

Investors hit Amazon recently, but that was driven more by the failure of their bet on the Fire Phone than it was on their basic strategy of investing in growth.

What Amazon Could Do Differently

Jeff ends with his recommendations to Amazon.

- Advocate for higher taxes for people living in Washington

- Recruit women aggressively from your competitors. Pay them a premium over men so you can get them and increase the diversity of Seattle

- Make donations to local Seattle charities to help the poor (and artists)

#1 is just ridiculous for Amazon to consider. Why would they do that?

#2 is interesting, but would not increase the number of women in tech – it would just move them from wherever they are to working at Amazon. It would make it a lot harder for other tech companies in Seattle to have any women working for them. The women gain (since they are getting paid more), but I’m not sure how this really helps

#3 Is basically Jeff saying: “Please Mr. Bezos: Can you take your money and give it to my personal causes?” Maybe Jeff’s causes are more important than what Bezos cares about (like say the $2.5M he donated to marriage equality). But given his ‘logical’ arguments in this piece I would bet on Bezos’ choices for donations over his at this point.

This post was pretty far from my normal posts on marketing and understanding data, but I’ve been asked about this article multiple times this week. I thought it was important to get my critiques down on paper. I think the arguments Jeff made this week will happen again in a different context in the future. I like the idea of being able to send people back to this post every time someone complains about the rent going up.

Thanks for giving me the opportunity and structure Jeff.

And thanks for reading all the way to the end of this monster.

I will try and respond to all comments below.

(Note on conflicts of interest: Other than the fact I live in Seattle, I have no financial interest in Amazon (except maybe as part of an ETFs that I am unaware of). I am also not a property owner in Seattle, so I have no personal motivation to see property prices go up. In fact higher property prices would eventually mean higher rent that would come out of my pocket. I’m also married so the gender ratio of the city doesn’t affect me as directly as it does the singletons in the city)